By Mitch Zacks

In previous columns, I’ve touched on the growing idea that globalization is in rapid decline. Recent events on the geopolitical stage appear to be hardening this narrative.

In quick succession, the U.S. shot down a Chinese spy balloon, President Biden made a surprise visit to Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced Russia would pause its participation in the nuclear-arms treaty with the U.S., and the Wall Street Journal reported that President Xi Jinping was planning a trip to Moscow in the spring. You don’t need to be an expert in geopolitics to conclude that tensions are escalating between the East and West.

Many prognosticators cite these events – and the lingering effects of the pandemic, which saw supply chains break down and shipping rates soar – as further evidence that globalization trends are set to reverse in the coming years and decades. Some ‘experts’ have all but written obituaries for globalization.

Many CEOs and investors are also worried. According to a survey published by the Harvard Law School, executives cited uncertain macroeconomic conditions and de-globalization as two of the top issues heading into 2023. A full 86% of investors and CEOs said that de-globalization is an imminent risk, which suggests that global supply chains and global trade are poised to unwind.

Put simply, the fears of de-globalization appear to be moving to new heights, which usually prompts me to ask the question if the fear of an economic outcome may outweigh the reality of it occurring. Any time that happens, the possibility of a positive surprise increases, which is essentially the formula for how markets climb a wall of worry.

I think we’re seeing this with the globalization story. While the narratives for de-globalization have increased dramatically over the last year or so, the data in global trade suggests that the opposite is happening.

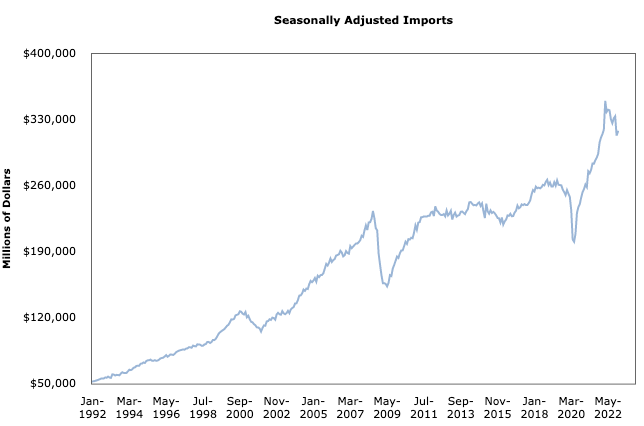

In 2021, global trade growth accelerated so quickly that it shot back up to its pre-2008 trendline. In 2022, global trade volumes reached a new record, posting figures nearly 10% higher than they were pre-pandemic. For the U.S., exports increased by 17.7% in 2022, while imports increased by 16.3%. As the charts below show, the U.S. is not exactly shutting itself off from the world economically.

U.S. Exports, Seasonally Adjusted (1992 – Present)

U.S. Imports, Seasonally Adjusted (1992 – Present)

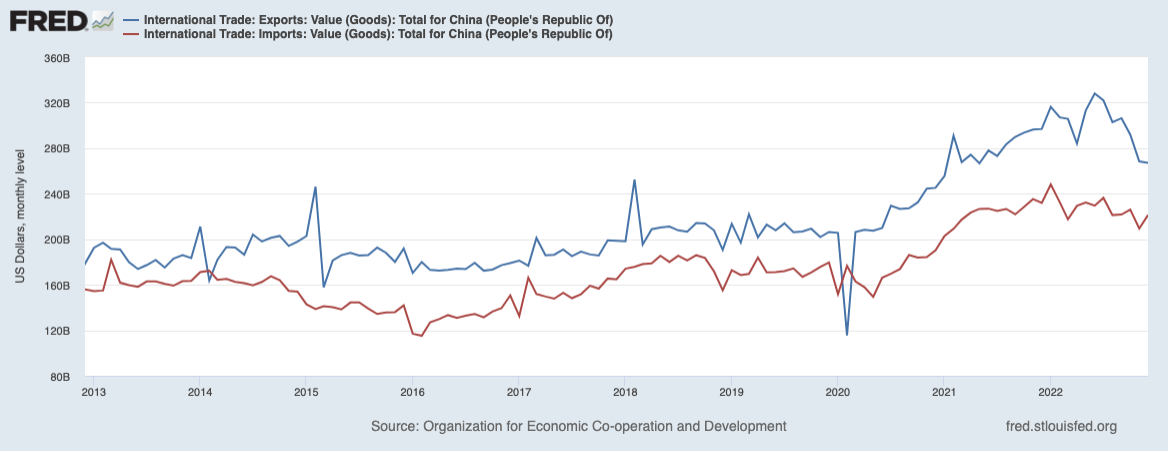

A big feature of the de-globalization argument is that the U.S. and China are at the cusp of a major decoupling, where economic cooperation and trade between the two will be a thing of the past. Yet as the two countries harden their stance toward the other, trade continues to rise: U.S. imports from China increased by 6.3% year-over-year in 2022, while exports rose by 1.6% year-over-year. Despite tariffs and aired grievances, total trade between the two countries reached a record $690.6 billion in 2022. Put simply, this is not evidence of de-globalization.

U.S. Imports (Red Line) and Exports (Blue Line) with China

In my view, what many in the media are labeling de-globalization is more of a ‘regionalization’ of supply chains and production, which some have referred to as ‘nearshoring.’ The basic tenet here is that supply chains can be strengthened by moving production closer to the end market, which also hedges against fluctuating shipping costs. That’s why we’ve seen Japanese, South Korean, and now Chinese companies establish factories and production in Mexico, so those goods can be labeled “Made in Mexico” and benefit from the free trade agreement. In this sense, moving production out of China is not de-globalization or some fundamental reworking of global commerce. It’s just global trade being restructured.

Bottom Line for Investors

Global trade as a percent of global GDP reached a peak of roughly 30% in 2013. As of the end of 2022, the figure stands at roughly 26%. This isn’t exactly global trade falling off a cliff.

While headlines often focus on tariffs, trade wars, and geopolitical tensions, behind the scenes there has been a proliferation of new trade deals and economic cooperation across developed countries and emerging markets. That’s a big reason why total global trade has gone up over the past several years, not down.

Iterating on a point I’ve made previously, globalization is not an on-off switch – it’s a complex and layered set of relationships between countries regarding trade, investment, financial systems, immigration, technological networks, supply chains, and so on. At any given time, a country may be seeing more cooperation in some of these areas, and less cooperation in others. But the suggestion that this cooperation is somehow going away seems far off base to me, and I think it’s another example of a global economic fear too far outweighing the reality of it.

Wenn du keinen Beitrag mehr verpassen willst, dann bestell doch einfach den Newsletter! So wirst du jedes Mal informiert, wenn ein neuer Beitrag erscheint!

±Der Beitrag A Quick Update on Globalization’s (Apparent) Demise erschien zuerst auf Grossmutters Sparstrumpf.